Abstract¶

This part of the documentation is still under construction.

It is intended to become a beginner-friendly introduction (and less of a draft of a research paper) to the threshold automaton model and a guide to what flavors of distributed algorithms can be modeled using threshold automaton model.

For a formal introduction consult the papers that introduced the threshold automata model alongside model-checking algorithms and applied the models to interesting algorithms 12345678910111213141516.

Also check out the previous state-of-the art model checker for threshold automata ByMC 1718 which unfortunately not maintained anymore and its website is no longer available. Still it contains features like a Promela which are not implemented in TACO.

This section of the documentation will be dedicated to introducing you to the theoretical models that are used in TACO. We will start by introducing the formal definition of the system model,i.e., threshold automata and their properties with a simple example. Then, Section: Model Checking Algorithms gives you a high-level overview of the three model checking algorithms implemented in TACO.

Distributed Algorithms and the Byzantine Generals Problem¶

Before jumping into the model lets first take a look at what kinds of algorithms TACO has been designed for.

So let’s start with the question: What are distributed algorithms? In essence, a distributed algorithm is an algorithm designed to be executed by a group of computers, also called nodes, that can communicate over some kind of network. Such algorithms are, for example, vital to scaling modern applications across many servers, often across multiple data centers, or even across the globe.

However, the distributed setting is hard, or in the words of Lesslie Lamport:

A distributed system is one in which the failure of a computer you didn’t even know existed can render your own computer unusable. 19

One key challenge that makes the distributed setting hard, is that not all nodes necessarily agree on the current view of the system. For example, initially the nodes of the system might not agree on which nodes are part of the system. To get a number of nodes to agree, one needs to solve the challenge of consensus.

The consensus problem asks a set of nodes to agree on a data value by exchanging messages. Many protocols have been developed for achieving consensus, a famous example used in many systems is Raft 20. However, in a real world distributed setting failures or incorrect behavior must be expected. Unfortunately, failures are often not simple crash-stop failures.

To model more complex failure behavior, the model of “Byzantine Faults” or byzantine behavior has been developed 21. A byzantine fault allows a node to behave arbitrarily, it is allowed to follow the protocol and stop responding, or it can actively try to sabotage correct nodes.

Achieving consensus in such a setting is especially hard, or even impossible if there are more than faulty nodes where is the number of nodes 21.

In general most of the consensus algorithms rely on some form of voting. This is where TACOs internal model comes in.

Threshold Automata¶

This section introduces the underlying theoretical framework of TACO, which are (extended) threshold automata (TA) 4516.

Definition:

A threshold automaton (TA) 45 is a tuple where:

is a finite set of locations.

is the set of initial locations.

is a finite set of shared variables over .

is a finite set of parameter variables over .

, the resilience condition, is a linear integer arithmetic formula over parameter variables.

is a set of rules, where a rule is a tuple such that:

.

is a conjunction of lower guards and upper guards. A lower guard is a constraint , with , , . An upper guard is a constraint .

The left-hand side of a lower or upper guard is called a threshold.is an update vector for shared variables.

is the set of shared variables to be reset to 0.

Most commonly, the parameter variables are , where is the number of processes, is a bound on the number of faulty processes, and is the actual number of faulty processes. This allows to express assumptions about the fraction of faulty processes in the system, e.g., .

If and no variables are reset, then the TA is called a monotonic TA (MTA). Otherwise we call it an extended TA (ETA)16.

Note that rechability is in general undecidable for ETA 1016. Consequently, TACO’s decision procedures become semi-decision procedures for the ETAs, which will in general not terminate when an ETA is safe.

Semantics¶

For a vector , we write if holds after substituting parameter variables with values according to . Then the set of admissible parameters is .

Once a TA is specified, the number of processes to be modeled must also be defined through the function (usually ).

Configurations. A configuration of a TA is a triple , where assigns a number of processes to each location, assigns a valuation to the shared variables, and assigns a valuation to the parameters. We say that a configuration is initial if and .

Paths. A rule is enabled in a configuration if and satisfies the guard . In this case, we say that where , , , and . A path is then a finite or infinite sequence of configurations such that for each there exists an enabled rule with . We denote by the set of all paths in the threshold automaton.

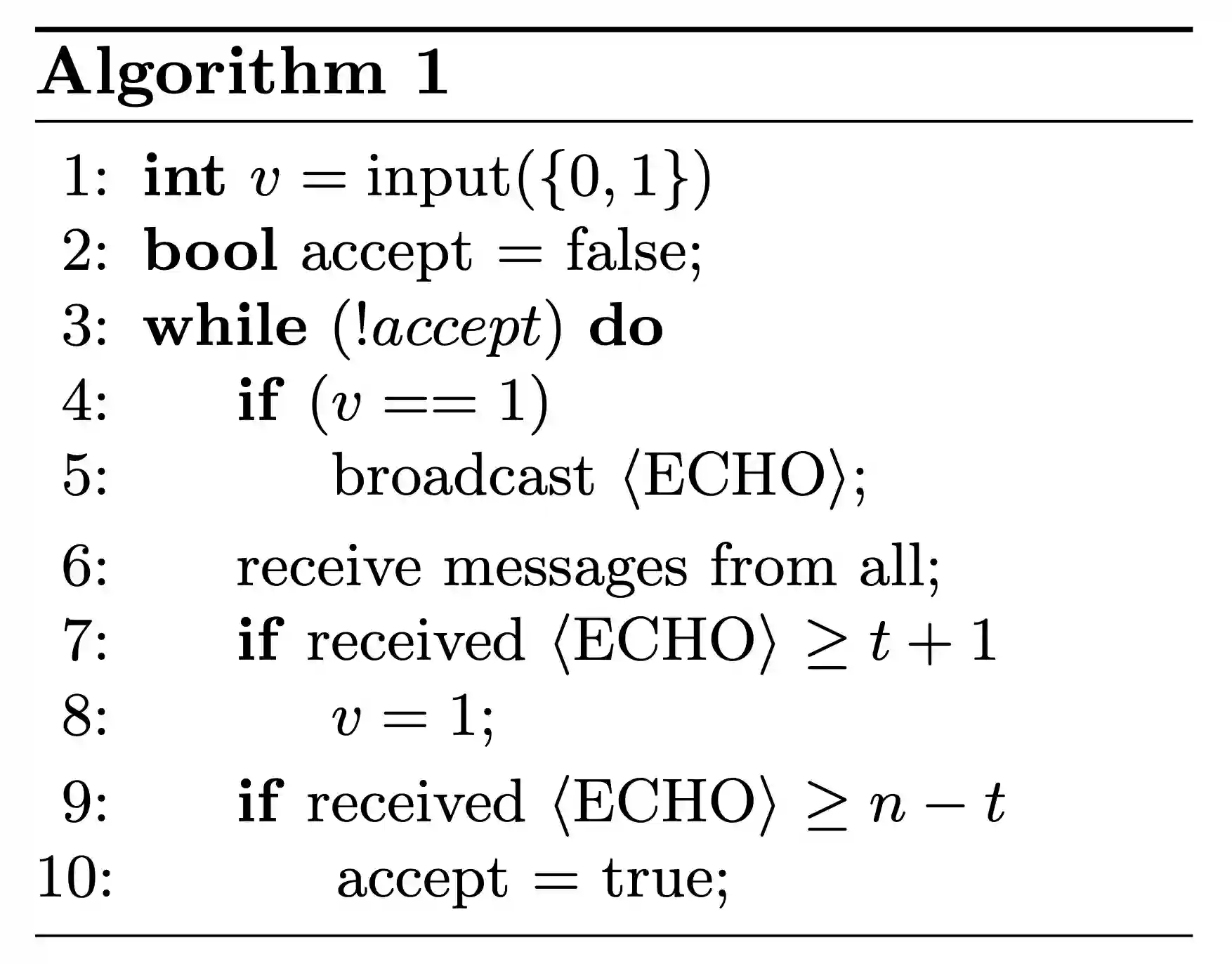

Figure 1:Pseudocode of a reliable broadcast protocol.

Example:

Figure 1 shows the pseudocode of a reliable broadcast, inspired by 22. In every round, processes with input will broadcast a message, then processes with will set if they received at least messages, and finally processes set if at least messages have been received. If is false at the end of the round, a new round starts.

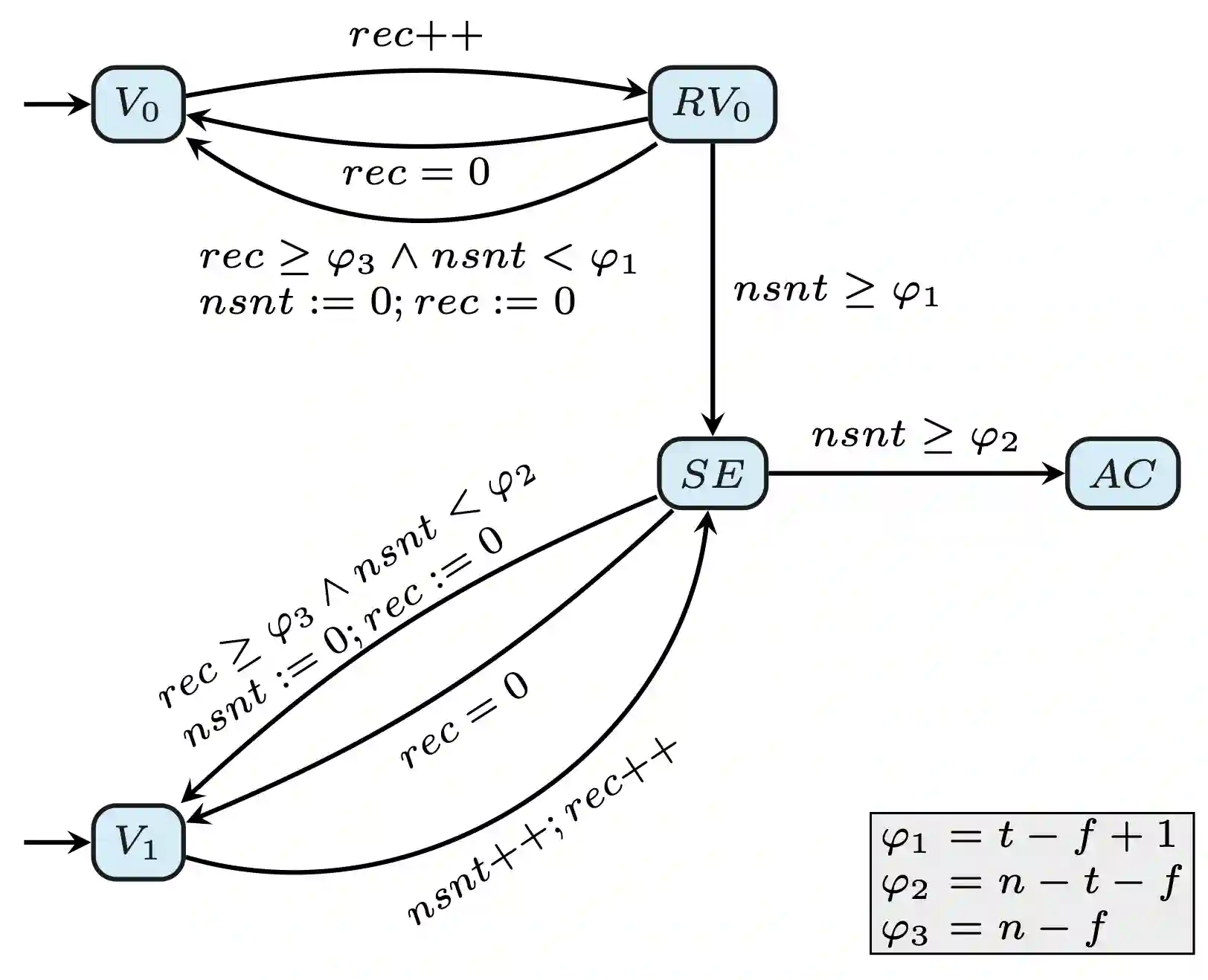

Example: Figure 2 depicts a TA for this algorithm, with , , , , and . A process in has input 1 and can move freely (there is no guard) to , incrementing both variables and to simulate lines 4–6 of the algorithm. A process in location has input 0 and can move to , incrementing to simulate line 6 (but not line 5, since the condition in line 4 evaluates to false). From , a process can move to if , simulating lines 7-8. Processes that started with already are in , corresponding to the fact that is not changed in line 8.

Note that instead of being , is chosen as . This prevents processes from making a transition based on messages from faulty processes, hence the TA represents the behavior of correct processes and the effect of faulty processes on correct ones. For more details on the role of , see 12.

Processes in can move to if , simulating lines 9-10. If and (this constraint corresponds to waiting long enough for all non-faulty processes to receive all messages), the condition in line 9 was not satisfied and a new iteration of the while-loop is started by moving back from to . The first process taking this transition will reset and , the others take the transition that does not change any variables. Similarly, processes in will move to to start the new round.

The condition is critical here to ensure fault-tolerance: if , then will be reachable even if all processes start in , violating the validity property.

Specifications on Threshold Automata¶

Basic Specifications¶

We consider two basic kinds of specifications: coverability, which refers to the notion of coverability that is widely used in parametrized verification, e.g., Petri nets 23 or VASS 24, and reachability.

Definition: The parametrized coverability problem is: Given a TA and a coverability specification , decide if there is a reachable configuration [1] with for all .

Definition: The parametrized reachability problem is: Given a TA and a reachability specification , decide if there is a reachable configuration with for all .

Usually, our specifications are definitions of error configurations, and therefore paths that reach them are called error paths.

¶

TACO supports safety specifications in the fragment of 725 that can be translated into reachability or coverability properties. Formally, the syntax we support is defined as follows:

where is a guard as defined in Threshold Automata and .

Furthermore, TACO also supports lower integer bounds on the number of processes in a specific location. The extended syntax is:

where and .

Example: One important property for consensus-based distributed algorithms is to check for validity, i.e., if no process received a specific value (e.g., 0), then no process should decide on that value. 1 specifies the valdity property in as follows:

To check if this property holds, TACO transforms this formula into a coverability specification that requires at least one process to be eventually in location while all correct processes initially start in location . If such a configuration is reachable, then the validity property is violated. Otherwise the property holds.

For further reading on the model of threshold automata, we refer the reader to 123456781713141516.

The next section Model Checking Algorithms will introduce the model-checking algorithms implemented in TACO.

A configuration is said to be reachable if there exists a path starting from an initial configuration and ending in .

- John, A., Konnov, I., Schmid, U., Veith, H., & Widder, J. (2013). Towards Modeling and Model Checking Fault-Tolerant Distributed Algorithms. In E. Bartocci & C. R. Ramakrishnan (Eds.), Model Checking Software - 20th International Symposium, SPIN 2013, Stony Brook, NY, USA, July 8-9, 2013. Proceedings (Vol. 7976, pp. 209–226). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-642-39176-7_14

- John, A., Konnov, I., Schmid, U., Veith, H., & Widder, J. (2013). Parameterized model checking of fault-tolerant distributed algorithms by abstraction. Formal Methods in Computer-Aided Design, FMCAD 2013, Portland, OR, USA, October 20-23, 2013, 201–209. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6679411/

- Gmeiner, A., Konnov, I., Schmid, U., Veith, H., & Widder, J. (2014). Tutorial on Parameterized Model Checking of Fault-Tolerant Distributed Algorithms. In M. Bernardo, F. Damiani, R. Hähnle, E. B. Johnsen, & I. Schaefer (Eds.), Formal Methods for Executable Software Models - 14th International School on Formal Methods for the Design of Computer, Communication, and Software Systems, SFM 2014, Bertinoro, Italy, June 16-20, 2014, Advanced Lectures (Vol. 8483, pp. 122–171). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-07317-0_4

- Konnov, I., Veith, H., & Widder, J. (2014). On the Completeness of Bounded Model Checking for Threshold-Based Distributed Algorithms: Reachability. In P. Baldan & D. Gorla (Eds.), CONCUR 2014 - Concurrency Theory - 25th International Conference, CONCUR 2014, Rome, Italy, September 2-5, 2014. Proceedings (Vol. 8704, pp. 125–140). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-662-44584-6_10

- Konnov, I. V., Veith, H., & Widder, J. (2017). On the completeness of bounded model checking for threshold-based distributed algorithms: Reachability. Inf. Comput., 252, 95–109. 10.1016/J.IC.2016.03.006

- Konnov, I. V., Veith, H., & Widder, J. (2015). What You Always Wanted to Know About Model Checking of Fault-Tolerant Distributed Algorithms. In M. Mazzara & A. Voronkov (Eds.), Perspectives of System Informatics - 10th International Andrei Ershov Informatics Conference, PSI 2015, in Memory of Helmut Veith, Kazan and Innopolis, Russia, August 24-27, 2015, Revised Selected Papers (Vol. 9609, pp. 6–21). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-41579-6_2

- Konnov, I. V., Lazic, M., Veith, H., & Widder, J. (2017). A short counterexample property for safety and liveness verification of fault-tolerant distributed algorithms. In G. Castagna & A. D. Gordon (Eds.), Proceedings of the 44th ACM SIGPLAN Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages, POPL 2017, Paris, France, January 18-20, 2017 (pp. 719–734). ACM. 10.1145/3009837.3009860

- Konnov, I., Lazic, M., Veith, H., & Widder, J. (2016). A Short Counterexample Property for Safety and Liveness Verification of Fault-tolerant Distributed Algorithms. CoRR, abs/1608.05327. http://arxiv.org/abs/1608.05327

- Konnov, I. V., Widder, J., Spegni, F., & Spalazzi, L. (2017). Accuracy of Message Counting Abstraction in Fault-Tolerant Distributed Algorithms. In A. Bouajjani & D. Monniaux (Eds.), Verification, Model Checking, and Abstract Interpretation - 18th International Conference, VMCAI 2017, Paris, France, January 15-17, 2017, Proceedings (Vol. 10145, pp. 347–366). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-52234-0_19

- Kukovec, J., Konnov, I., & Widder, J. (2018). Reachability in Parameterized Systems: All Flavors of Threshold Automata. In S. Schewe & L. Zhang (Eds.), 29th International Conference on Concurrency Theory, CONCUR 2018, September 4-7, 2018, Beijing, China (Vol. 118, p. 19:1-19:17). Schloss Dagstuhl - Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik. 10.4230/LIPICS.CONCUR.2018.19

- Bertrand, N., Konnov, I., Lazic, M., & Widder, J. (2019). Verification of Randomized Consensus Algorithms Under Round-Rigid Adversaries. In W. J. Fokkink & R. van Glabbeek (Eds.), 30th International Conference on Concurrency Theory, CONCUR 2019, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, August 27-30, 2019 (Vol. 140, p. 33:1-33:15). Schloss Dagstuhl - Leibniz-Zentrum für Informatik. 10.4230/LIPICS.CONCUR.2019.33

- Stoilkovska, I., Konnov, I., Widder, J., & Zuleger, F. (2020). Eliminating Message Counters in Threshold Automata. In D. V. Hung & O. Sokolsky (Eds.), Automated Technology for Verification and Analysis - 18th International Symposium, ATVA 2020, Hanoi, Vietnam, October 19-23, 2020, Proceedings (Vol. 12302, pp. 196–212). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-030-59152-6_11

- Konnov, I., Lazic, M., Stoilkovska, I., & Widder, J. (2023). Survey on Parameterized Verification with Threshold Automata and the Byzantine Model Checker. Log. Methods Comput. Sci., 19(1). 10.46298/LMCS-19(1:5)2023

- Konnov, I., Lazic, M., Stoilkovska, I., & Widder, J. (2020). Survey on Parameterized Verification with Threshold Automata and the Byzantine Model Checker. CoRR, abs/2011.14789. https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.14789

- Balasubramanian, A. R., Esparza, J., & Lazic, M. (2020). Complexity of Verification and Synthesis of Threshold Automata. https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.06248